D&D.Sci, problem 2 (preface)

This post is part of my "dnd.sci" series.

Old tools

In part one I limited myself to spreadsheet builtins only. I wanted to curb my perfectionism, and it did help, but I quickly ran into the limitations of the system.

- LibreOffice has no out of the box support for histograms

- The spreadsheet model of computation is not friendly to data of unknown dimensions1

- Advanced tools, like neural networks, random forests, and k-NN classifiers/regressors, would be… interesting to import, to say the least

The dealbreaker is point two. There are workarounds (with INDIRECT or named ranges), but they are less than satisfactory.

New tools

Jupyter

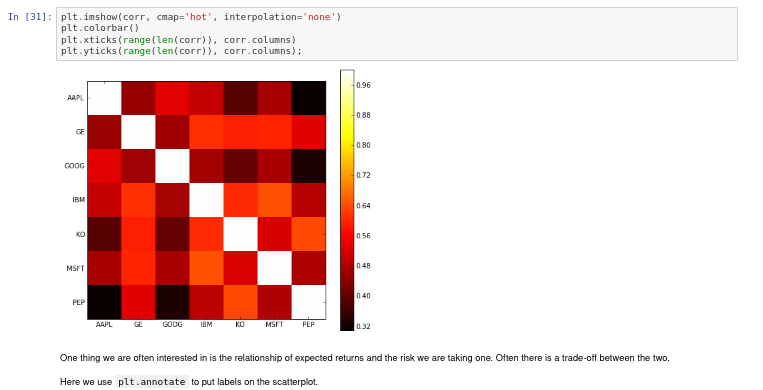

The weapon of choice for data analysis these days are Jupyter notebooks, with analysis code either on Python or R. Notebooks let you string together text, code, and output (including graphical output) into a single linear document. They look quite snazzy.

Taken from Thomas Wiecki's "Financial analysis in Python".

Notebooks are meant to solve the exact problem I have: I need something beefier than spreadsheets, but your garden variety shell is going to start spasming if you try to mix in text and graphics with your code.

Tradeoffs

Power comes at a cost. Notebooks are way more complicated than spreadsheets.

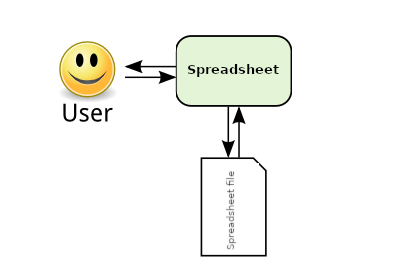

A spreadsheet is a single file that you handle with a single program. The spreadsheet program may be a behemoth like Microsoft's Office suite, or something much lighter like Gnumeric, but working locally with a single app is the default. Something like Google Sheets is an extra twist on a fundamentally simple model.

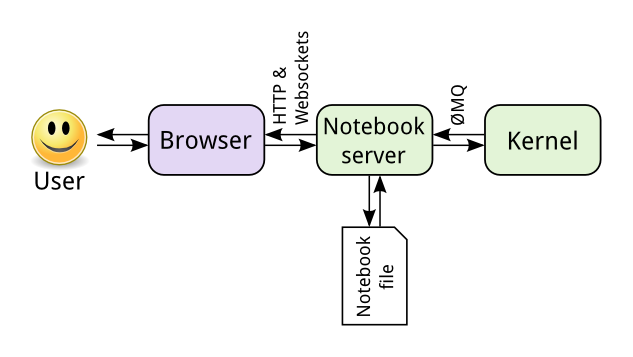

If I understand correctly, a notebook is a single file encapsulating code and data. The file's format is an open standard2 derived from JSON (don't be intimidated by the .ipynb extension, you can open it with a text editor and read it). The file is read by a notebook server, which delegates the actual operations described by the notebook to a computation kernel and the presentation to the user's web browser3.

Oh Gods, why is there a web server involved!? I just wanted spreadsheets but better!

I haven't found the rationale for this spelled out anywhere, but I can make an educated guess:

- Scientific computation is fragmented over several languages so language agnosticism is a must. This is why computing kernels are a thing.

- "Big data" moves a lot of money, so the ability to delegate computation to a cluster is a must for some users.

- The system is meant to minimize friction. This means that the user interface needs to be interactive, but also stupid easy to turn into a script.

- Simultaneously developing interactive GUIs for a web service across multiple operating systems strongly favors coding for the browser.

That is a lot of added complexity. I probably won't be publishing my work as notebooks. I may publish the notebooks separately.

Language of choice

As for language, I'm going with Python. I have some experience working with it, and library support for statistics is really strong. Sorry R, you are probably the better language; we'll get acquainted some other time.

Boxes upon boxes upon…

When I last installed Jupyter notebooks several years ago, I had lots of trouble with conflicting Python versions. Plus some tools are not happy to be hosted on Arch, or Ubuntu, or Windows, or whatever. It seems that this problem is under control now with things like the conda package manager, but. I'M. SO. TIRED. Of doing cleanup for misbehaving tools. Of fixing broken linux installs. Of getting stuck for days on "simple" tasks. Even if the Python ecosystem has got its shit together, there is no guarantee that some other tool won't fuck things up for me.

So screw it. I'm stuffing every project worth a damn to me into its own virtual machine. This way, as long I've gotten VirtualBox to run I can just spin up the relevant vm and get back to work. I can afford the processor and storage overhead, and I cannot put into words how demoralizing it is to run into broken tools over and over, for more than a decade, and have nothing I can do about it because this is isn't my fucking job and I have shit to do.

The installation experience

I'm currently running Manjaro Linux (XFCE edition) as both host and guest. I had some installation pains on the host, and I managed to run into an XFCE bug on day one, but overall I'm happy with the experience. I've had no trouble with Manjaro as a guest.

Installing VirtualBox on Manjaro was surprisingly tricky, but Manjaro's VirtualBox wiki page sorted me out.

Jupyter notebooks were a cinch. I installed pip (Python3 is already installed), ran pip install jupyterlab, and everything worked as advertised. Running pip install pandas got pandas working.

Accessing a service running in the vm from the host system is simple enough. I use NAT with port forwarding4.

Now that the tools are up, I can get started with the analysis proper.

-

Spreadsheets represent programs as tables, where each cell contains an expression. An expression can be a value (eg

100), a computation over values (eg=10+20+70), or a computation over other expressions (eg=SUM(A1:A3)). To reference other cells we need to know the addresses of the cells; if you are building a program to analyze data that you don't know the shape of (unknown number of rows/columns), the language itself forbids you from talking about it. ↩ -

https://nbformat.readthedocs.io/en/latest/format_description.html ↩

-

https://docs.jupyter.org/en/latest/projects/architecture/content-architecture.html#the-jupyter-notebook-interface ↩

-

The service running in the guest needs to be served to all interfaces, not loopback. Jekyll serves itself to localhost (127.0.0.1) by default. It is usually possible to serve to all interfaces by serving to the IPv4 magic address (0.0.0.0). You can control the visibility when you set up port forwarding by changing the host IP address. An IP of 127.0.0.1 makes the service visible on the host only. Omitting the host address, or setting it to the IPv4 magic address makes the service available to the LAN. Weirdly, you cannot set the host address to "localhost"; in my experience this is just an alias for 127.0.0.1, but VirtualBox takes issue with that form. ↩